I did not think I was acting foolishly. As an entitled American, I showed up at JFK with a Taiwanese passport that expired in 1998. Why would anyone stop me from attending my father’s funeral? I thought I was above Covid, above laws and regulations, above CDC, CECC, and whatnot.

My flight was scheduled to depart at 1:25 a.m. Even if I was foolish, I was punctual. I arrived precisely three hours before departure, following the recommended guideline. In all the scenarios I had played in my head, I foresaw the hurdle of the border crossing to take place in Taoyuan International Airport. I was surprised, therefore, when the border was only a few steps from the revolving door where my husband dropped me off.

“You cannot go to Taiwan without a visa,” a customer service agent said matter-of-factly.

“I am aware of it. My father just passed away, and I don’t have time to get a visa because the funeral is this Saturday. I have a valid U.S. passport and a Taiwan passport, but it expired. Can I speak to someone in charge?”

I had rehearsed these lines over and over, except for the part about speaking to someone in charge.

“I can ask my supervisor, but she will tell you the same thing.”

A South Asian, he was a stern, young millennial that seemed more worried about doing a poor job of border control than helping a matron in distress.

“Alright. I was told if I state my reason at the border, it will be considered. I have all the documents with me, including my father’s death certificates and funeral notice.”

As it turned out, no one cared to review these morbid papers.

He paused for a brief second and took my Taiwan passport to a Chinese lady in plain clothes. After some exchange, he brought a form back to me.

“Fill it out.”

This form was entirely written in Chinese and intended for travelers with an expired Taiwanese passport. My eyes lit up, “Does it mean you are trying to help me?” I asked.

He nodded half-heartedly, without any verbal commitment.

I quickly filled out the form, not as an American but as a Taiwanese. Having to write my name in three simple characters felt oddly familiar.

As soon as I handed the form back with my passport to the Chinese lady in plain clothes, I texted my husband and brother. “They are giving me a hard time here.”

The young man then asked me to step aside and wait. I frown at being told to step aside in places with lines. It is like being cast into purgatory, where you watch the lucky ones get ahead and finish their business.

“Where should I wait?”

“Anywhere. I will find you.”

He will find me? Even in the lady’s room if I shall end up there? I had a feeling he wanted me to disappear.

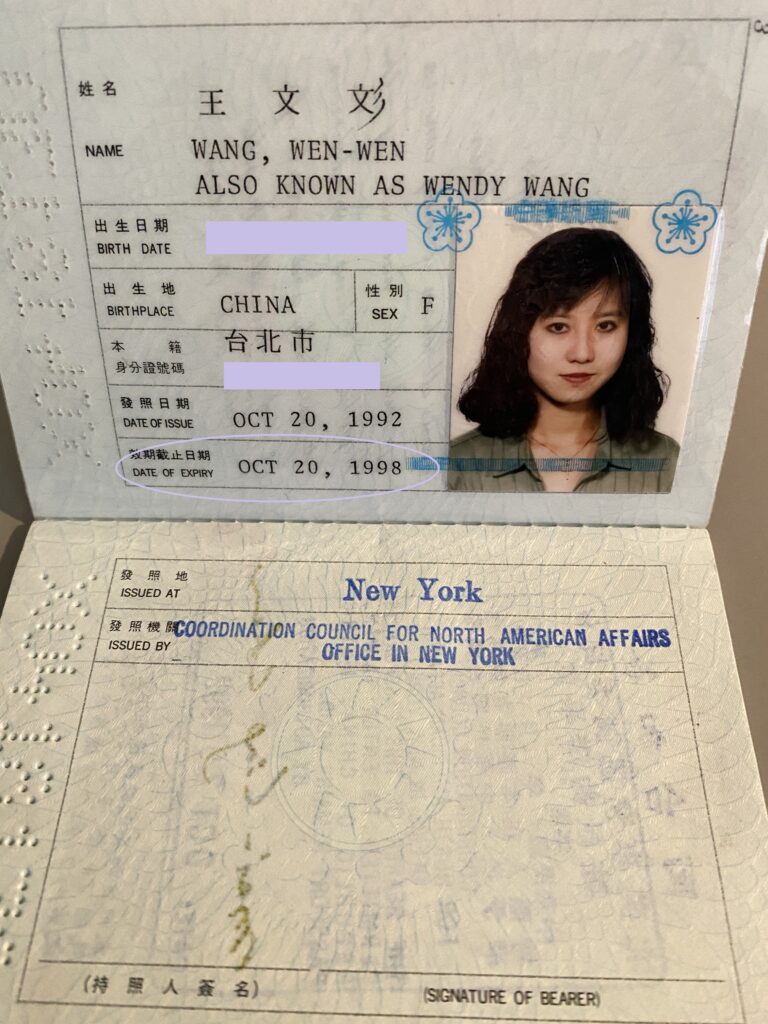

It was close to 11 p.m., and the reality had set in. I would be at the mercy of many strangers from this point forward. When both my husband and brother texted back with praying hands and praying words, it made me see the enormity of the situation. Showing up without a visa and with a Taiwan passport that expired during the Clinton administration and when President Teng-hui Lee was at the helm had backfired on me.

I spotted a row of seats occupied by a large Latino family. A baby was crying inside her stroller, refusing to be soothed. Two girls were playing tag, running in circles. It was a bustling scene of robust family life, but I had no patience to relish such a scene. I hoped for them to clear out because I was beginning to feel weary. I watched them hug it out, cheek to cheek, as they finally separated after an emotional farewell.

I plopped myself down at the end of the row. I scanned the hall and looked for the young man and the lady that took my Taiwanese passport. He had his head down, looking busy. I longed for someone to come with a signal of approval from Taiwan. Yet, at that moment, the world seemed to have forgotten about me.

Empty seats in a busy airport don’t remain vacant for long. A Latino family of three rolled in with enough cardboard boxes to build the Great Wall of China. These boxes were stacked so high that they completely obstructed my view of the airline counter. I was holding onto the young man’s promise that he would find me, and how can he find me if he can’t see me?

So I continued my wait in front of the wall of boxes. Another hour passed.

My husband texted me a few minutes before midnight and asked to talk. I had no updates for him. I told him I would follow up at 12:10 a.m. Meanwhile, a burly middle-aged lady in uniform walked by.

“The terminal is closing. What are you all doing here?” The security officer seemed irritated too by the Great Wall of China in the middle of her terminal.

The man that appeared to be the dad had just finished chomping down a cup of uncooked ramen, and his wife was frantic, looking for words to explain.

“What time is your pick-up?” The lady in uniform was determined to get to the bottom of it.

A girl that looked no more than twelve years of age stepped forward. In perfect English, she replied, “Our ride is three hours away.”

“Three hours away!” I can hear myself saying it in unison together with the security officer. “You can’t wait here. The terminal is closing.”

While the family scrambled to move, I quietly slipped away from her field of view as I bravely walked toward the EVA counter.

I approached the only agent present and asked for an update.

“Still waiting for Taiwan,” said the agent with long black hair tied in a ponytail, “You should have applied for an entry permit before coming here.” Her words were cold, deflating an already punctured soul.

“Entry permit? How in the world would I know to apply for such a document when I couldn’t even get anyone at Taiwan Economic and Cultural Office (TECO) to answer the phone?” I mumbled, hoping the world could hear me.

It was approaching 12:20, just one hour before the scheduled departure. Just then, I saw the Chinese lady who had taken my passport. She quickened her steps and walked towards me. My heartbeat too quickened.

“I am still waiting on Taiwan. Just another ten minutes, okay?”

“Oh, okay. Do you think I can make my flight? It’s only an hour away.” I am the kind of traveler who would rather spend an hour lounging by the gate than barreling down the concourse right before takeoff.

“If I hear back in ten minutes, you will make your flight.”

Even with selective listening and a general sense of optimism, the word if was hard to ignore.

A few minutes later, a throng of people, a family of five, actually, rushed towards the counter, huffing and puffing. The anxiety on their faces baffled me. They really believed they would miss their flight with one more hour till takeoff.

This family checked in their many pieces of luggage without a hitch and proceeded to the security checkpoint. Even these “American” rugrats made it through the border. I, on the other hand, born and raised in Taiwan, had no permission to go back to bury my father.

I pressed for another update.

“I will start the process to check you in to save time,” the agent in ponytail suddenly decided to be helpful. Eagerly, I lifted my near-empty suitcase onto the weighing station as she printed out a luggage tag. She then started to communicate with someone through a walkie-talkie.

The muffled exchange could be heard as she continued to talk through the transmitter.

“No word from Taiwan,” she shook her head and waited for a directive. “Okay, I got it.”

“I am sorry. We can’t let you board the plane.” The agent avoided eye contact with me. She stripped off the luggage tag and pushed the suitcase back towards me. The lady with my passport reappeared. With a helpless look, she gave me back my expired passport.

I could hardly believe what was happening: they were turning me away. They were expecting me to call someone to pick me up at 1 a.m. from JFK.

I have been building a dam since I found out my father died – a dam to wall off the flood of emotions and tears. I was not going to look weak or sad. I was going to be calm and tough.

“Is that it? What does it mean? Am I just going to cancel this whole thing. They scheduled my dad’s funeral three weeks after his death, keeping his body in the morgue, just so that I could be there. I guess it’s just not going to happen, then?”

The dam broke, and tears rolled down my cheeks.

“You can try to go to TECO on Monday and see if you can get a permit.” The lady that had my passport gently suggested.

“But is there a guarantee I can get a permit the same day? Then I still have three days of quarantine…I just don’t think I can go through with it.” By then, I was clearly crying in front of all these strangers.

“Let me try something.” The agent in a ponytail signaled at me before making a call. She got through and started to talk.

“Could you please do me a favor? I have a passenger here that needs to get on the flight to go to her father’s funeral. Could you check your e-mail and see if you have the passport images that we sent you? It’s for a Ms. Wang. They kept on telling us they couldn’t open the files. Could you please check it for me right now? We are about to take off and I need to close down the counter soon.”

With one hand on the phone, she proceeded to process my luggage the second time.

This was the same agent that spoke icily about the entry permit. Instead of being tough with me, she was now tough on whoever she was speaking to. I could hear her urging and pressuring the person to take action on my behalf.

“Ms. Wang, I am still waiting for them to give you the approval. I will walk you to the gate. If they don’t approve, I will have to walk you back, okay?”

She then called out to the luggage handlers, “Last passenger here!” I felt good to be called the “last passenger.” To belong on this passenger list was the only thing I wanted. I glanced at this agent’s badge and saw the name: Cindy Zhang.

Right at that critical moment, a petite, young woman in a pair of ripped jean shorts and Nike sprinted up towards the counter, barely catching her breath. She exasperatedly told Ms. Zhang about her three-hour flight delay and that she ran through eight terminals to get here. She was close to hyperventilating as she stuttered and couldn’t finish her sentences.

“Breathe. I am still here. Don’t worry,” I said. A mother’s instinct kicked in even under duress. I later found out she was flying back to have her father’s tombstone relocated.

After checking in our luggage, we were both told to head toward the security checkpoint.

The TSA officers were about to lock the gate when they saw two hapless Chinese women. They immediately reopened the lane and waved us through.

Ms. Zhang followed us. She was still on the phone, walking briskly through the concourse. I could hear her talk about me.

“Did you go to Taiwan after 1994 on the U.S. Passport?” Surprised by the question, I answered, “Yes, I did…in 2001.”

Cindy went on to explain to the person on the phone that my Taiwanese passport included an “also known as Wendy” designation and that I had taken on my husband’s surname. I could hear a change in her tone as she started to sound upbeat.

She hung up the phone, turned to me and said, “Just make sure you have 400 TWD. After you land, you will pay for the entry permit.” Though still matter-of-factly, Ms. Zhang had let her humanity shine through.

“I don’t have any Taiwanese currencies on me, but I will beg and borrow if I have to.”

She chuckled at my reply and went on to explain, “It all depends on who you get on the phone. Sometimes you get a nice boss, and they would approve with just an I.D. And sometimes you get a tough boss, and it will take forever.” Knowing it was within her power to chase down an answer, she decided to go above and beyond to get me the approval.

“Can I hug you?”

I could tell this Cindy was not a hugger, but I’ve got to do the right thing. So I embraced an EVA Traffic Officer at Gate 8. Words could not express how much I appreciate this woman.

It was already 1:20 a.m. A line of passengers was still waiting to get on the plane. I later found out my luggage was loaded onto the plane two days later. Perhaps the ground crew was still as confused as I was and decided it was best to wait.

A 15-year-old that left her homeland in 1987 has come back as one of its own at age 50. A long-lost and even estranged daughter was picked up by the people that had never forsaken her. I reinstated my Taiwanese citizenship on the day my American-born son turned seventeen. I have a lot to catch up on. To start, I’ve got to learn to speak Mandarin the Taiwanese way.